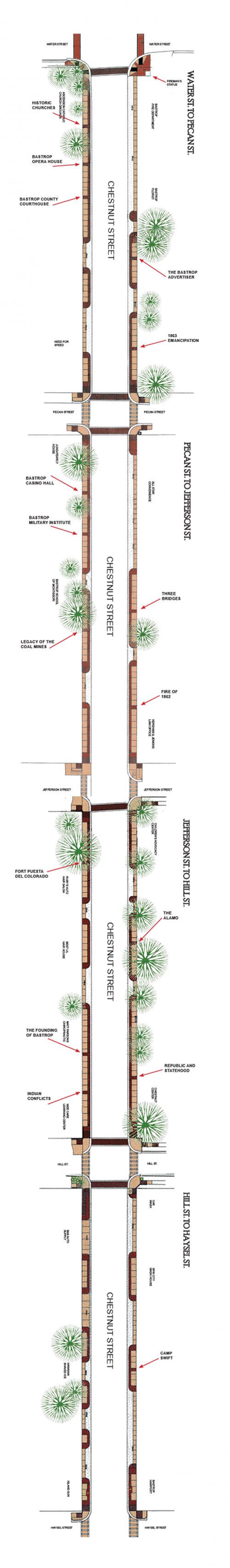

Bastrop Medallion Tour

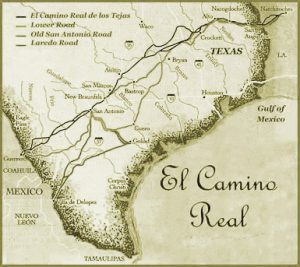

El Camino Real de los Tejas (The King’s Highway) has existed for more than 300 years and the Old San Antonio Road section came directly through the heart of present-day Bastrop. |

This thoroughfare extended from the arid lands of Mexico through Texas’ rolling hills and piney woods to Natchitoches, Louisiana. It was instrumental in the settlement, development, and history of Texas, connecting important Spanish missions and posts, capitals of provinces, and forts. The trails changed through time as the traveler’s course was influenced by weather, Indian relations, terrain and modes of transportation. Its routes were the arteries that kept Texas alive, enabling settlers to carry information vital to the province – orders for its administration, reports of danger and appeals for help – and served as the principal avenues of commerce throughout the colonial period. In the wake of Spaniards who marked the trails came such men as Moses Austin and his son, Stephen Fuller Austin, Jim Bowie, Davy Crockett, and Sam Houston. The route of the Old San Antonio Road throughout present Bastrop County is closely followed by State Highway 21. El Camino Real de los Tejas was designated as a National Historic Trail in 2004.

Map Legend

- Historic Churches

- Bastrop Opera House

- Bastrop County Courthouse

- The Bastrop Advertiser

- 1863 Emancipation

- Bastrop Casino Hall

- Bastrop Military Institute

- Three Bridges

- Legacy of The Coal Mines

- Fire of 1862

- Fort Puesta Del Colorado

- The Alamo

- The Founding of Bastrop

- Indian Conflicts

- Republic and Statehood

- Camp Swift

- Kerr Community Center

- Bastrop State Park

- The Railroad

- Early Bastrop Industry

- Bastrop Historic Homes

- Fairview Cemetery

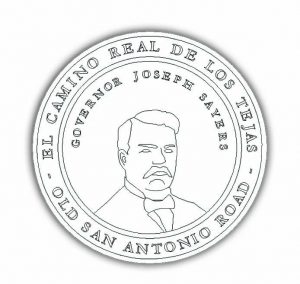

- Governor Joseph Sayers

- Primera Iglesia Bautista

- Deep in the Heart Art Foundry

1. Historic Churches

Religion figures prominently in the early history of Bastrop, with congregations gathering outdoors or wherever space was available. As the community grew, so did the need for facilities serving these congregations. The communitie’s oldest congregations include the following:

The congregation that became the First United Methodist Church was established in 1835.

The First Baptist Church of Bastrop was organized in 1850.

The first Lutheran Church in Bastrop was established in 1856.

The Bastrop Christian Church existed as early as 1857.

In 1864, a Catholic parish was established, and is now known as Ascension Catholic Church.

The Calvary Episcopal Church was organized in 1869 and constructed what is now the oldest church building in Bastrop in 1883.

The Paul Quinn African Methodist Episcopal congregation was established in Bastrop in 1876 by Rev. Joseph Morgan.

The congregation of the Primera Baptist Church began in 1884; however, a building was not erected until 1928.

2. Bastrop Opera House

On land purchased in 1866 by R. A. Green, his son, D. S. Green, along with P. O. Elzner, a leading merchant in Bastrop, built the Bastrop Opera House. The building, considered to be one of the finest of its type in Texas, opened in 1889 with an elegant dress ball. Bastrop became the center of culture and, in turn, the Opera House became the center of entertainment. Elzner became the sole owner in 1901, then sold the building to W. J. Miley and W. B. Ransome. It was known as the Arion Opera House Association from 1909 to 1913 when Mr. and Mrs. Earl Erhard purchased it. In 1942, they sold it to J.G. Long who remodeled the building for a movie house called the Strand Theatre. The Strand was in operation throughout World War II, entertaining local citizens and Camp Swift soldiers. In 1958, the property was deeded to a youth organization and the building became known as the Teen Tower where teenagers danced to the tunes of the 1950s and 1960s. In the late 1970s and 1980s the building was renovated once again and now offers performances of all types, returning to its rightful place as the center

3. Bastrop County Courthouse

The first Bastrop County Courthouse, called a “meeting house,” was built in 1840 and was jointly owned by the county and city of Bastrop. The second, a two-story structure built in 1853, served the citizens until it burned in 1883. It was replaced the next year with the courthouse which stands today. Designed by Austin architect Jasper Preston with associate architect Frederick Ruffini, the building was built of red brick and stone. The original design of the building included gables over each entrance, decorative caps on the corner pavilions, and a central clock tower with three tiers. In 1923/4, the building was “modernized” by C. H. Page and Bros. The original roof and pediments were removed, replaced with a flat roof with parapets on the corners and over the entrances. The stone cupola was replaced by a shorter one of copper. The entrance porticos were altered and the façade was covered with a yellow-beige colored plaster. The interior was also renovated at this time. The courthouse, with a later addition, now sits next to a modern annex and the historic 1891 jail.

4. The Bastrop Advertiser

In June 1852, Bastrop’s Colorado Reveille newspaper ended its brief run. In December of that year, William J. Cain, age 19, and his brother, Thomas C. Cain, 17, both of Mississippi, bought the press and printing materials and started the Bastrop Advertiser. Even though paper had to be brought from Houston in ox wagons at times and the wagons were often delayed, the paper came out each Thursday (during the years it was published once a week) even if it had to be printed on wrapping paper as was the case once or twice. T. C. Cain took over the business when his brother retired, and his son, T. W. Cain, followed him as owner and editor. Except for a period during the Civil War, the paper has continuously served Bastrop’s residents. In 1920, T. W. Cain sold it, thus ending a run of 2/3 of century under the direction of three members of the Cain family. Through the years, the paper has focused on the area’s news and rich history. Today, the Bastrop Advertiser is known as the oldest bi-weekly newspaper in Texas.

5. 1863 Emancipation

Juneteenth, also known as Freedom Day or Emancipation Day, is an annual holiday in 14 states and Texas is the primary home of Juneteenth celebrations which are traditionally celebrated on June 19. The celebration commemorates the 1865 announcement of the abolition of slavery, making a reality in Texas Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863. On June 19, 1865, Union Major General Gordon Granger read a general order to the assembled citizens in Galveston stating that “all slaves are free,” and Texas thus became the last state to learn of the Confederate surrender and the freeing of the slaves. The announcement sparked immediate celebration in the black community, and each year this date is commemorated with state-wide and local celebrations. This event ushered in a challenging, often violent period of change in which the social, cultural, economic, and political order of Texas was radically transformed. With the power of the Federal government backing the new reality, freed slaves gained a measure of justice and equality that established them as full participants in the life of Bastrop County. Resistance from conservative whites retarded this progress, but the ideals of Juneteenth kept alive the drive for full and equal participation by African-Americans.

6. Bastrop Casino Hall

One of the county’s oldest cultural centers was the Casino. This building, erected circa 1848, began as a dwelling and kitchen and still stands at the corner of Farm and Fayette Streets in Bastrop. It later housed one of Bastrop’s early schools and much of the town’s entertainment. The Casino was an incorporated institution organized by the Casino Association in 1867. It soon became the cultural center of Bastrop with a membership of almost every citizen in town. The girls and boys attended dances there, dressed in their finest apparel, and the music was the best available. Dinner was served in true southern style. Concerts, banquets, stage plays, and all forms of cultural diversions of the day were performed in the Old Casino with people coming from all over the county and state to attend the performances. The Casino and its accompanying acreage were sold on October 25, 1891, to the German-American School Association, making a center that would elevate the morals, and the educational and cultural values of the citizens of Bastrop. The school was relatively short-lived, however, since the Bastrop Public School opened in 1894.

7. Bastrop Military Institute

In 1851, Professor William J. Hancock was hired as headmaster of a new school, the Bastrop Academy with 132 students. Before the Civil War, the institution functioned in both preparatory and collegiate capacities. Studies included mathematics, geography, the natural sciences, Latin, and Greek, as well as surveying and civil engineering. In 1857, the Academy was converted into the Bastrop Military Institute under the direction of Col. Robert Thomas Pritchard Allen, a West Point graduate, civil engineer, mathematics professor, and Methodist preacher. Students included the son of then Governor Sam Houston, and Joseph D. Sayers, later governor of Texas. By 1861, its faculty consisted of four professors and three assistants. Students paid $230 for a term of 40 weeks. During the Civil War attendance tapered off as cadets joined the war, and the school eventually closed. Because Reconstruction policies temporarily prevented the operation of military schools in the South, after the Civil War the school resumed a non-military format until the summer of 1868 when the James brothers received permission to restructure it using a military format (within two years they moved it to Austin.) The 1892 H. P. Luckett House stands on the site of the Academy/Institute which was razed earlier that year.

8. Three Bridges

The first bridge across the Colorado River at Bastrop, built of iron and constructed in 1889 at a cost of $45,000, was known as the “Old Iron Bridge”. It ended the era of ferries which had been in use since the 1830s. The bridge, 1,268 feet in length, was originally a toll bridge, but was later purchased by the county and made free for travel. With automobiles becoming the normal form of transportation after World War I, a new bridge of greater capacity was needed to handle the increasing traffic between Houston and Austin. The new bridge, financed by bonds issued by Bastrop County and by federal funds disbursed by the Texas State Highway Department, was built by the Kansas City Bridge Company in 1923. The final cost of construction was $167,500. The bridge was opened for use in January 1924. It extends 1,285 feet with three steel truss spans, each 192 feet in length, supported on concrete piers. This bridge, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, is one of the earliest surviving uses of the Parker truss in Texas. Existing simultaneously for a while, the Old Iron Bridge was sold and torn down in the early 1930s. The steel bridge is now reserved for pedestrian and bicycle use, with a new highway bridge, built in 1992, next to it.

9. Legacy of the Coal Mines

Among Bastrop County’s most productive industries during the early 1900s was that of coal mining. The county contained extensive deposits of lignite coal which was first commercially mined in 1898 by Martin Glenn. Glenn, with his son-in-law, founded a corporation known as the Glenn-Belto Coal Company. In 1905, J. C. Phelan, the son-in-law of Colonel Hunter, owner of the Texas & Pacific Coal Company, opened the second mine on the property of W. B. Ransome, three miles north of Bastrop, and called it the Phelan Mine. The dozen or more mining communities in the area were populated with over 1,000 miners and their families, predominately Mexican-American. Most of these communities were self-sufficient, with their own stores, schools and churches. Phelan Mine even had its own brass band which played for church festivals and fiestas. The descendants of these early Mexican-Americans contribute to Bastrop’s success today. Lignite operations in the county reached their peak in the post war years of 1918 through 1920. From a peak annual production of over half a million tons, the tonnage dwindled rapidly until the last mine was closed in 1944.

10. Fire of 1862

Bastrop residents who fled the advancing Mexican army in 1836, returned to find their town had been largely put to torch by the Mexican Army and Indian raiders. The residents of Bastrop set about rebuilding in a steady process of growth for the next twenty-five years. Characteristically, early buildings were of wood (readily accessible and milled locally) but such construction left the buildings vulnerable to fire. In 1862, Bastropians were dealt another devastating setback because of a fire that destroyed almost half the business district, Main Street between Chestnut and Pine. For this reason, many buildings in the downtown area were then made from brick. A fire on January 18, 1883, completely destroyed the Bastrop County courthouse, but luckily all county records were saved. In 1890, another fire began at the livery stable at the corner of Main and Spring Streets. Nineteen horses perished in the flames. Volunteer firemen braved the heat and saved the newly built First National Bank building, a sturdy brick structure, which acted as a buffer to protect the buildings farther to the south.

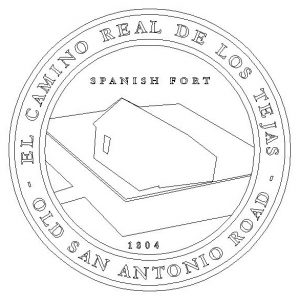

11. Fort Puesta del Colorado

The first non-Native American settlement in this area was made to protect the commerce on the Old San Antonio Road. Manuel Antonio Cordero y Bustamente in 1805 ordered troops to be stationed at the ford on the Colorado River, where a stockade was built in the southern portion of present Bastrop near the river, and named Puesta del Colorado. Zebulon Pike saw it on June 16, 1807, and described a small Spanish station, consisting of a guard of dragoons and a few lodges of Tonkawa Indians. How many soldiers were sent to the post has not been determined; however, the number, when combined with troops on the Guadalupe and San Marcos rivers, totaled 30. A claim for livestock lost while moving artillery from Nacogdoches to Bexar and dated October 26, 1807, may indicate that the post on the Colorado was abandoned by then, but if not, it was gone by the time of the Mexican War for Independence from Spain a few years later.

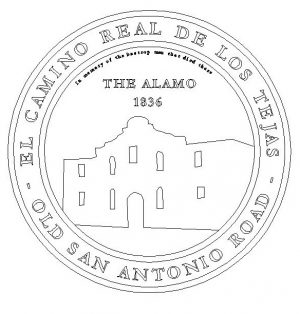

12. The Alamo

The 1836 Battle of the Alamo was a pivotal event in the Texas Revolution. Following a 13-day siege, Mexican troops under General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna launched an assault on the Alamo mission at San Antonio de Bexar (San Antonio). When the Alamo fell, 12 Bastropians died alongside Davy Crockett. After the fall of the Alamo, settlers in Bastrop gathered up their farm animals and other possessions and fled in a mass exodus called “the runaway scrape,” as a detachment of Santa Anna’s advancing forces, led by General Gaona, followed closely behind. The young town was looted by the Mexican Army and by Indian raiders. Not much was left of the town when its residents returned after Santa Anna’s defeat at San Jacinto, an event that secured Texas’ independence. Bastrop County, with Bastrop as county seat, began to rebuild and it was among the original 10 counties established by the Republic of Texas in 1836. Though it was a strong contender for the permanent Capital of the new Republic, that distinction went to the village of Waterloo, 30 miles farther up the Colorado River, now renamed “Austin” in honor of Stephen F. Austin.

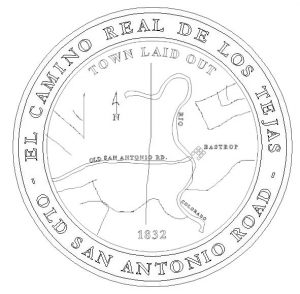

13. The Founding of Bastrop

Bastrop’s setting – the intersection of the Colorado River and the Old San Antonio Road (about 600 yards downstream from the present Highway 71 bridge) was hand-picked by Stephen F. Austin. In 1821, when he traveled from Missouri to San Antonio to solidify his father’s claim to colonize Texas, he followed this road and used the crossing to ford the river. Riding through the pines, he crested the ridge to the east and observed a four-mile wide valley below him – well watered, fertile, and possessed of excellent timber. Six years later, when he needed to create a town in the upper regions of his colony, he recalled this site and applied for a land grant containing the area so he could build a community around the crossing. Upon approval, Austin influenced Land Commissioner Miguel de Arciniega to name the proposed town after the Baron de Bastrop, who had greatly aided him in colonizing Texas. On June 8, 1832, Arciniega laid out the town and formally named it Bastrop. The section nearest the river crossing began to develop as an important place of commerce, government, and social life. Major flooding in 1836, however, devalued this area as overflowing water from the swollen Colorado inundated it. Town leaders moved the business district to the bluff area around today’s Main and Chestnut Streets.

14. Indian Conflicts

Before European explorers entered the picturesque Colorado River basin, the area was populated by itinerant, indigenous Indian groups who hunted game, gathered food, traded goods and sought refuge from native foes. Of many tribes in the area, a few – like the Tonkawa – were peaceful and assisted the settlers, especially because of a common enemy. That enemy, the Comanche, determined to eliminate those encroaching on their traditional hunting grounds, resisted Anglos with considerable ferocity. In 1833, one of Bastrop’s pioneers, Josiah Wilbarger, was among a surveying party of five that was attacked by Comanche about four miles east of present Austin, Texas. Two settlers were killed and scalped; two managed to flee to the home of Ruben Hornsby. Wilbarger was scalped and left for dead but managed to survive, crawling into a nearby stream to wash his wounds and drink. Wilbarger’s companions thought he had been killed, but later that night Hornsby’s wife envisioned Wilbarger in a dream sitting under a tree. She gave her husband a description of the tree and insisted that the men go to rescue him. Wilbarger was found there the next day. Though he never completely recovered from the wounds, he lived for 11 years following the attack.

15. Republic and Statehood

When Mexico won its independence from Spain, Mexican authorities allowed organized immigration from the United States, and by 1834, over 30,000 Anglos lived in Texas, compared to only 7,800 Mexicans. In 1835, when President Antonio López de Santa Anna abolished the Constitution of 1824, granting himself enormous powers over the government, wary colonists in Texas began forming Committees of Correspondence and Safety. The Texas Revolution officially began on October 2, 1835, in the Battle of Gonzales. Although the Texians originally fought for the reinstatement of the Constitution of 1824, by 1836 the aim of the war had changed. The Convention of 1836 declared independence on March 2, 1836, and officially formed the Republic of Texas. On February 28, 1845, the U.S. Congress passed a bill that would authorize the United States to annex the Republic of Texas. On March 1, U.S. President John Tyler signed the bill. On October 13, 1845, a large majority of voters in the Republic approved both the American offer and the proposed constitution that specifically endorsed slavery and emigrants bringing slaves to Texas. This constitution was later accepted by the U.S. Congress, making Texas a U.S. state on the same day annexation took effect, December 29, 1845 (therefore bypassing a territorial phase.

16. camp swift

Camp Swift, an army training facility located approximately seven miles north of Bastrop, began operation in June of 1942, following the bombing of Pearl Harbor six months earlier. The camp was named after Major General Eben Swift, a World War I commander and author, and initially consisted of 2,750 buildings accommodating 44,000 troops. As World War II progressed, the camp reached a maximum strength of 90,000 troops and at different times included the 95th, 97th, and 102nd Infantry Divisions, the 10th Mountain Division, the 116th and 120th Tank Destroyer Battalions and the 5th Headquarters, Special Troops, of the Third Army. At that time, Camp Swift encompassed over 52,000 acres of hilly uplands and flat lowlands and was the largest army training and transshipment camp in Texas. It also housed 3,865 German prisoners of war. Following the war, Camp Swift was decommissioned as an army camp and much of the land was returned to its original owners, sold and committed to public purpose. The government retained 11,700 acres as a military reservation. That land now houses part of the Texas National Guard, a medium security federal prison and a University of Texas Cancer Research Center.

17. kerr Community center

Robert A. Kerr moved to Bastrop sometime prior to 1880. He was elected to the Texas House of Representatives in 1881. He also served on the Bastrop school board, helping to establish Emile School, one of the earliest high schools for black students in Texas. Robert’s brother, Beverly, was a versatile musician and bandleader of Kerr’s Orchestra. He and his wife, Lula, also an excellent musician and the first primary grade teacher at Emile School when it opened in 1892, saw the need for a social center for the African-American community. In 1914, they built what was then called “Kerr Hall.” This two-story frame structure became the heart and soul of Bastrop’s black community, serving as its social, civic, recreational and educational focal point. Over the years, many entertainers performed at the center, including Roosevelt Williams (The Grey Ghost), a master at the piano. During World War II, the army renovated the center as a United Service Organization (USO) to serve black soldiers at Camp Swift. The building and adjacent park, now fully restored, continues to serve as a legacy to the Kerr family and Bastrop’s African-American community, and brings the entire community together, regardless of race or ethnicity.

18. bastrop State Park

The “Lost Pines” of Bastrop County had enough available potential park land – 3,504 acres – to host two Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps from 1933 to 1937. The Corps, a Depression Era recovery initiative of the federal government, cleared and seeded the land and built rustic buildings from native stone and hand-hewn timbers. Based on federal policy, this helped give the impression that their efforts had little impact on the area’s natural resources. With timber and locally quarried Mt. Selmon Stone, young men, mostly from families on relief, constructed a scattered complex of 14 cabins, walls around the entrance, a guard house, and an assembly building known as “the Refectory.” Architect Arthur Fehr, who directed most of the work, embraced the design principles of the National Park Service, which emphasized harmony with the surrounding landscape. The superb walnut, oak, cedar and pine woodwork on the Refectory, including a massive beamed ceiling, and cabins artfully nestled within the park’s loblolly pine forest, enhance the natural setting. A swimming pool and golf course were built under another New Deal agency, the Works Progress Administration.

19. the railroad

Integral to rebuilding after the Civil War was a railroad to Bastrop. Though concerted efforts failed, the Houston and Texas Central Railway in 1871 was completed across the northern part of the county connecting Austin with Houston. The towns of Paige, McDade, and Elgin were born as a result. Citizens were forced to travel and transport goods between Bastrop and the nearest station, McDade. Local entrepreneurs, realizing that financial vibrancy demanded it, persisted in seeking a rail company that would lay tracks through Bastrop. When an especially promising opportunity arose in the mid-1880s, the city council offered 8,000 acres of corporation land to any railroad that would build a line through Bastrop and within a mile of the courthouse. Eventually, the Taylor, Bastrop, and Houston Railway Company was formed, the city and other subscribers provided enough incentive that a branch line was built. It arrived in Bastrop from the north in December 1886 on the exact location of the rail lines a few yards from here. After reaching Bastrop, the company continued to lay track southeastward, across the river to present Smithville and beyond. Soon, the company was absorbed by the Missouri, Kansas and Texas (Katy) Railroad. Having a rail line in Bastrop ended the need to travel to McDade and transformed the economic and social life of the town.

20. early bastrop industry

“King Cotton” arrived in Bastrop County in 1837, supporting Bastrop’s economy for decades. Another significant industry began in 1838 when the Bastrop Steam Mill Company began operation. This mill initiated lumbering activity that reached a peak in the mid 1800s with Bastrop mills supplying lumber to other settlements, including Waterloo, soon to become the capitol of the Republic of Texas (later renamed Austin). When available timber declined, agriculture and ranching became the primary means of earning a living. Economic stimulus came to Bastrop County in 1871 in the form of the Houston and Texas Central Railroad, responsible for the establishment of a number of area communities. The Missouri Kansas Texas (the Katy) Railroad, which came through Bastrop, followed in the late 1880s. Coal and lignite mining thrived in the early years of the 20th century and the discovery of oil in the county in 1913 led to years of drilling. In the 1920s, clay deposits added Bastrop County to the list of communities making bricks, most notable the north-county town of Elgin which became the “Brick Capital of the Southwest.”

21. bastrop historic Homes

As the village grew to a town of importance during the 1800s and early 1900s, adventurers, farmers, merchants and professional men came to the Bastrop area from many American states and European countries. Today, Bastrop is fortunate in that many homes built in this era still grace the City’s historic district’s tree-canopied streets. Numerous styles of early Texas architecture are represented from unpretentious board-and-batten cottages and farm houses to elaborate mansions and plantation homes. This diversity of architecture adds tremendously to the charm of Bastrop and, in turn, reflects diversity in its population. Bastrop boasts of more than 130 historical buildings and sites – the largest number per capita in the state – listed on the National Register of Historic Places by the Texas Historical Commission. These fine vintage homes, many beautifully restored, reveal how early Bastropians once lived. Several serve as inns, allowing visitors an opportunity to experience the life and times of early Bastrop.

22. Fairview Cemetery

The City of Bastrop was first laid out by the Mexican government in 1832. Included in the initial community plat was a 12-acre cemetery overlooking the colony. The first known grave was that of Sarah Wells (died 1831), a child of early colonist Marty Wells. The first marked grave is that of Crescentia Augusta Fischer (died 1841), a German immigrant who tried to escape a yellow fever epidemic in Galveston but died in Bastrop six days after her arrival. A guardian angel monument watches over the “war babies,” infants fathered by Camp Swift soldiers during World War II. Fairview Cemetery is the final resting place of notable Bastrop citizens, including elected state and national officials, and veterans of major military conflicts dating to the War of 1812. Texas Governor Joseph Sayers is one of only two governors not buried in the Texas State Cemetery in Austin; he is buried in the family plot here. Although headstones feature prominent names like U.S. Congressman George Washington ‘Wash’ Jones and early African American legislator Robert Kerr, the cemetery is also a link to many generations of Bastrop residents, all of whom contributed to Bastrop’s rich history.

23. governor joseph sayers

Joseph Draper Sayers was born September 23, 1841, in Grenada, Mississippi to Dr. David and Mary Sayers. After Mary died in 1851, Sayers moved to Bastrop, Texas with his father and younger brother, William. He attended the Bastrop Academy from 1852 to 1857 and the Bastrop Military Institute from 1857 until the Civil War broke out in 1861. He then joined the Confederate States Army’s Fifth Texas Regiment, reaching the rank of major in 1864. After the war, he returned to Bastrop where he studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1866. Sayers represented the Bastrop district in the Senate in 1873 and was chairman of the Democratic state executive committee from 1875 to 1878, then served one term as lieutenant governor. In 1884 Sayers was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, serving until 1898, representing the then 9th and 10th districts, encompassing Bastrop. He was elected the 22nd governor of Texas in January 1899. While governor, several disasters struck Texas including the 1900 Galveston hurricane. Sayers left office in January 1903 and focused on his law practice. He died May 15, 1929, and is buried at Fairview Cemetery in Bastrop.

24. primera iglesia bautista

The history of this church began in 1894 when congregations of Hills Prairie and Smithville missions of the First Mexican Baptist Church in Waelder, Texas combined to establish an independent church in Bastrop: Primera Iglesia Bautista. On March 1, 1903, that union was officially organized and recognized as a Baptist church. In 1906, the small congregation obtained property near Gutierrez and Paul Bell Streets and built a small wood-frame church building. In 1912, two congregants attended a Baptist convention in San Antonio in search of a pastor and hired young Paul Carlyle Bell who would lead the church for 30 years. In 1922, the church purchased the rest of the block on which the original church was sited. On the newly acquired land, the congregation built a larger church structure which was completed in 1928. The older building became an orphanage for Hispanic children in 1930, closing in 1936. The church was also the site of a Bible Institute for Hispanics from 1925 to 1941. Today, the congregation of the Mexican Baptist Church, rechartered and renamed Primera Baptist Church, conducts services in both Spanish and English.

25. deep in the heart art foundry

The Bastrop History Medallions were sculpted and cast by the skilled craftsmen at Deep in the Heart Art Foundry, located in Bastrop, Texas – one of five foundries in the U.S. capable of creating monumental bronzes using lost wax casting. Under the leadership of owner Clint Howard, these talented men and women worked from historical photos and a host of other reference materials to sculpt unique medallions, each depicting a significant part of Bastrop history, as well as one universal design that is used throughout the downtown area. The foundry was established in 1980 in downtown Bastrop. Since that time, the foundry has moved to larger quarters in the Bastrop Business Park and has grown to become one of the nation’s leading art foundries, serving the casting needs for sculptors across the country and around the world. Deep in the Heart Art Foundry is open for guided tours by appointment Monday through Saturday by contacting Fireside Gallery adjacent to the foundry. For information, call 512-321-7868 or visit www.DeepintheHeart.net.